I'm pretty sure I've discussed chimerism on here before (I know I've at least talked about mosaicism), but in case I haven't, the idea has nothing to do with Frankenorganisms created by smushing bits of other animals together. A genetic chimera is an organism that has collections of cells with at least 2 different sets of DNA. We get half of our DNA from one parent and half from the other, but normally all of our cells get the same "mom set" and the same "dad set," so instead a chimera has more than one "mom set" and more than one "dad set". Usually this happens when two eggs are fertilized by separate sperm and later fuse, creating an individual with some cells with "mom set A" and "dad set A" from the first fertilized egg and other cells with "mom set B" and "dad set B" from the second.

Currently, the FDA is mulling over a technique for test-tube embryos that involves a sort of chimerism in the sense that the embryo produced would have three parents. This would be achieved by taking just the mitochondria from a donor egg, replacing the mother's egg mitochondria with those of the donor, and then fertilizing the egg and continuing on as normal for in-vitro. It's not quite as obvious a chimera because all that's being added from the third parent is a set of organelles, but mitochondrial diseases are a pretty big problem considering they control energy production. They also house their own DNA, so these diseases are passed on from mother to child. As such, being able to replaced genetically faulty mitochondria in an otherwise healthy egg cell would be a huge help for the child later in life.

What I find interesting is the amount of backlash this is facing. Anything involving embryos is going to get religious groups riled up. Is it natural? Well, no. (Of course, "natural" is a stupid word to begin with, but that's aside the point.) But technically at the point of the swap, the egg isn't even fertilized yet, so you're in no way harming any sort of embryonic form, and this is a procedure that could save kids who would've otherwise inherited these mitochondrial diseases a lot of hassle later on. The other fear is that if we can "tweak" DNA like this, scientists will abuse this to create designer babies by only taking the best DNA from however many parents. I'm pretty sure that's not how it works. This is only dealing with a very small subset of DNA that isn't even inherited in the same way that the rest is, so the mechanism is completely different.

I know this won't get far with all the fear mongering going around, but if it were to go through, we'd be doing a lot of people a lot of favors.

27 February 2014

26 February 2014

ScienceOnline dedicates a weekend to revolutionizing science on the Internet

For my mobile and social media journalism class, we have to keep tabs on journalists and leaders in our beat, and because my beat is science (I know, shocker), I have a list of science people I follow on Twitter and Facebook and such. This week, I've seen a lot of the hashtag #scio14, so I decided to check it out, and I've decided that I needed to hitchhike my way down to Raleigh for ScienceOnline Together. The event, which started today with tours of various science hotspots in the city, starts with sessions tomorrow and continues through Saturday.

The nonprofit that runs it, ScienceOnline, seeks to gather experts from around the field of science communication (teachers, journalists, researchers, etc) to talk about how to best get their ideas out online. This weekend's event was started in 2007 and has since branched out to additional conferences that cover more specific parts of science communication, such as the brain, climate, and a teen conference. They also run ScienceSeeker, an aggregator of science news and blogs; their current tally is at more than 1,200 sites.

In addition to all the silliness, sass, and snark I'm getting via Twitter from the event (Discover Mag blogger Kyle Hill is particularly fun to follow), I'm enjoying the lineup of sessions they have for this weekend. They have a few on specific topics such as women in science or non-English science communication, how to make science accessible to the average joe (and subsequently how to make the average joe think more scientifically), and how to utilize online resources for science and science communication. If that's not enough of an incentive, they also have breaks in which participants get together for games and even a costume gala.

Unfortunately for me, registration has been closed for a while, as they only take about 450 people. There's also the issue of my lack of money (it's 350 bucks), transportation (more money I don't have), plus that thing called class. But if I can get in next year…

The nonprofit that runs it, ScienceOnline, seeks to gather experts from around the field of science communication (teachers, journalists, researchers, etc) to talk about how to best get their ideas out online. This weekend's event was started in 2007 and has since branched out to additional conferences that cover more specific parts of science communication, such as the brain, climate, and a teen conference. They also run ScienceSeeker, an aggregator of science news and blogs; their current tally is at more than 1,200 sites.

In addition to all the silliness, sass, and snark I'm getting via Twitter from the event (Discover Mag blogger Kyle Hill is particularly fun to follow), I'm enjoying the lineup of sessions they have for this weekend. They have a few on specific topics such as women in science or non-English science communication, how to make science accessible to the average joe (and subsequently how to make the average joe think more scientifically), and how to utilize online resources for science and science communication. If that's not enough of an incentive, they also have breaks in which participants get together for games and even a costume gala.

Unfortunately for me, registration has been closed for a while, as they only take about 450 people. There's also the issue of my lack of money (it's 350 bucks), transportation (more money I don't have), plus that thing called class. But if I can get in next year…

Tequila byproducts can be used to create plastic

One of the major issues we face today is that of waste. We produce things more quickly than we can take care of the trash, and in a society that embraces planned obsolescence, more of that waste is trickier to dispose of safely. Even waste from food production is becoming a problem, but the tequila industry at least may have an option for their future.

A study (heads-up: it's in Spanish) from the University of Guadalajara found that the bacterium Actinobacillus succinogenes, found in cow stomachs among other places, can take the sugars from byproducts of tequila production to create succinic acid. This might not sound too exciting until you know that succinic acid is one of the components of biodegradable plastic. All cells produce it, but it's normally derived chemically from petroleum when used to make plastic.

The main obstacle here is one of scaling: Actinobacillus succinogenes can only produce 20 grams of succinic acid from one liter of tequila production waste, and the lab that did the study only has about 3 liters of acid from their trials. However, plans to increase the volume are in the works once scientists can recreate the small-scale environment in a larger container to support production; a separate plant in Barcelona is already working on industrial-scale succinic acid production.

If this can get off the ground on a reasonable scale, I think this is a great idea. I'm not sure of exact numbers regarding the self-sustainability of it, but if the tequila industry were to at least produce some of their bottles with plastic made from their own byproducts, that would be pretty awesome. That's less plastic that has to be created from petroleum, which is something we have enough problems with already, plus it's biodegradable, which completes the cycle.

A study (heads-up: it's in Spanish) from the University of Guadalajara found that the bacterium Actinobacillus succinogenes, found in cow stomachs among other places, can take the sugars from byproducts of tequila production to create succinic acid. This might not sound too exciting until you know that succinic acid is one of the components of biodegradable plastic. All cells produce it, but it's normally derived chemically from petroleum when used to make plastic.

|

| Model by Ben Mills from Wikimedia Commons via public domain |

If this can get off the ground on a reasonable scale, I think this is a great idea. I'm not sure of exact numbers regarding the self-sustainability of it, but if the tequila industry were to at least produce some of their bottles with plastic made from their own byproducts, that would be pretty awesome. That's less plastic that has to be created from petroleum, which is something we have enough problems with already, plus it's biodegradable, which completes the cycle.

23 February 2014

STAP cell study to go under investigation

You may remember the post I wrote on Feb 3 about the group of Japanese researchers who turned somatic cells into stem cells by treating them with acid. It turns out that the RIKEN Center is conducting an investigation on this study because subsequent trials have proved inconclusive in recreating the data.

(Sorry for the link dumping there, but all of the links were related to that one sentence.)

As someone who has gone through many labs in school, I fully understand not being able to recreate the results of a study. Especially in middle and high school, carelessness or other mistakes are usually the culprit, but even correctly measured and conducted experiments flop; sometimes I'm convinced they don't work just to spite you. I've even been in at least one lab in which everyone's experiments flopped for no reason. However, it's unlikely that so many that are professionally done would have come up with inconclusive results.

One of the tenets of research is that it's replicable, and this not-so-good track record is a little troubling. Did they leave out part of the procedure? Were there different measurements? Was there an issue of translation? I imagine these are all things that the RIKEN Center will look into, but the crowdsourcing aspect could also help rule this out. I'm going to avoid a cooking analogy here because I don't really want to associate food with test-tube mice, but the scientists checking this out on their own could pretty easily tweak different material amounts or types to see if the changes produce something worth while.

(Sorry for the link dumping there, but all of the links were related to that one sentence.)

As someone who has gone through many labs in school, I fully understand not being able to recreate the results of a study. Especially in middle and high school, carelessness or other mistakes are usually the culprit, but even correctly measured and conducted experiments flop; sometimes I'm convinced they don't work just to spite you. I've even been in at least one lab in which everyone's experiments flopped for no reason. However, it's unlikely that so many that are professionally done would have come up with inconclusive results.

One of the tenets of research is that it's replicable, and this not-so-good track record is a little troubling. Did they leave out part of the procedure? Were there different measurements? Was there an issue of translation? I imagine these are all things that the RIKEN Center will look into, but the crowdsourcing aspect could also help rule this out. I'm going to avoid a cooking analogy here because I don't really want to associate food with test-tube mice, but the scientists checking this out on their own could pretty easily tweak different material amounts or types to see if the changes produce something worth while.

22 February 2014

New kakapo conservation site looks hopeful

I could probably do an entire month on fun animals in New Zealand because there are so many and they are all so awesome, but if there's one everyone should know, it's the kakapo. Kakapo are one of the three remaining species of the parrot superfamily Strigopoidea, which also includes the kaka and kea. They're the heaviest parrot and flightless, but they have very strong legs and are good at climbing and hiking. They're also very hard to find, not only because their mottled green feathers blend in well with foliage but also because there are only about 120 left. What's worse is that 120 is a really good number compared to when they couldn't find any in the 1970s.

Conservation efforts have been ramped up, and now two islands have been established specifically as kakapo sites, Codfish Island and Little Barrier Island. The birds, all of whom are named, are monitored closely and provided with supplementary food when their standard diet of rimu berries runs low. One kakapo in particular, Sirocco, serves as the spokesbird of New Zealand conservation efforts: a respiratory infection as a chick left him more or less imprinted on humans, so he tours the country every so often to promote conservation efforts.

In addition to mating with TV show hosts, kakapo mating is of particular importance because of the small population size. It only occurs once every few years, and egg viability is often a problem with the reduced genetic pool. In 2012, the program transferred a few kakapo pairs to Little Barrier Island to determine its viability as a reduced-monitoring site, and researchers were pleasantly surprised to see that there are eggs at some of the nesting sites on the island this year. The birds here don't receive the supplemental feeding due to the reduced-monitoring trial, but the presence of fertile eggs shows that the site is a success thus far.

Conservation efforts have been ramped up, and now two islands have been established specifically as kakapo sites, Codfish Island and Little Barrier Island. The birds, all of whom are named, are monitored closely and provided with supplementary food when their standard diet of rimu berries runs low. One kakapo in particular, Sirocco, serves as the spokesbird of New Zealand conservation efforts: a respiratory infection as a chick left him more or less imprinted on humans, so he tours the country every so often to promote conservation efforts.

In addition to mating with TV show hosts, kakapo mating is of particular importance because of the small population size. It only occurs once every few years, and egg viability is often a problem with the reduced genetic pool. In 2012, the program transferred a few kakapo pairs to Little Barrier Island to determine its viability as a reduced-monitoring site, and researchers were pleasantly surprised to see that there are eggs at some of the nesting sites on the island this year. The birds here don't receive the supplemental feeding due to the reduced-monitoring trial, but the presence of fertile eggs shows that the site is a success thus far.

20 February 2014

Female chemists start boycott of all-male paneled ICQC in June

While it's nice to the extent that it regularly gives me something to talk about, the continuing sexism in science especially obnoxious. I posted a link on Twitter and my personal Facebook earlier in the week regarding the flak female sci-fi writers get for writing about things that aren't sparkles and rainbows and ponies, and female science reporters aren't treated any better, as demonstrated by science blogger Emily Graslie's "fan" mail. It's also no surprise that women are still underrepresented in STEM, but even those who have climbed the academic ladder are facing ignorance.

Salon published an article today about a boycott of the International Congress of Quantum Chemistry, an event held by the International Academy of Quantum Molecular Sciences because all 24 speakers on the initial and now-redacted list were male. This may have been expected, say, 50 years ago when women weren't as prevalent in such a field, but the directory hosted by the Women in Theoretical Chemistry shows more than 300 women in tenured positions or equivalent. Only four of the 110 members of the Academy are women, and only two of the 102 talks in the past three years were by women.

I'm aware that diversity for the sake of diversity is controversial. One of the responses to the boycott was that you can't possibly make every panel equal in all demographics; you pick the best people regardless of who they are. However, the numbers as they stand now aren't representative of the field. There are more women, and these women are of equal standing in their field. Even the "old white guys" that dominate the field think these highly-qualified scientists have gotten snubbed. As University of Minnesota professor Chris Cramer points out:

Salon published an article today about a boycott of the International Congress of Quantum Chemistry, an event held by the International Academy of Quantum Molecular Sciences because all 24 speakers on the initial and now-redacted list were male. This may have been expected, say, 50 years ago when women weren't as prevalent in such a field, but the directory hosted by the Women in Theoretical Chemistry shows more than 300 women in tenured positions or equivalent. Only four of the 110 members of the Academy are women, and only two of the 102 talks in the past three years were by women.

I'm aware that diversity for the sake of diversity is controversial. One of the responses to the boycott was that you can't possibly make every panel equal in all demographics; you pick the best people regardless of who they are. However, the numbers as they stand now aren't representative of the field. There are more women, and these women are of equal standing in their field. Even the "old white guys" that dominate the field think these highly-qualified scientists have gotten snubbed. As University of Minnesota professor Chris Cramer points out:

"What if it's a woman who has the next big breakthrough idea that advances our field dramatically? And, what if she can't get that idea recognized as quickly precisely because implicit bias slows appreciation for her scholarship? You'll suffer, too, as you won't be able to offer your clients a service that you otherwise would have become more rapidly aware of."I'm not saying this as a STEM-involved female but as a human being who values human rights: give these women (and the rest of lady STEMers) their due. The only thing separating them from the guys is the lack of support.

18 February 2014

WaPo stops publishing science and health press releases

This was definitely a post I had to reread. Last week, the Knight Science Journalism Program at MIT uncovered the Washington Post's practice of publishing press releases from universities as articles in the paper, and today the paper announced that it will cease this practice. I initially misread the headlines and thought that WaPo was cutting all science content, which really upset me, but upon reading the articles, I'm not only glad that they're ending the practice but also a little annoyed that it was a thing in the first place.

One of the things beaten into students' heads - and I'm talking all students, not just journos - is that plagiarism in any form is bad, be it copying, lacking citations, or even just being really bad at paraphrasing. In journalism, this is especially bad because our tenets (such as those of the SPJ) include accountability and independence, both of which are undermined by using the content of others without permission.

These press releases, such as this one from the University of Zurich about attractive features and success, are labeled as being from the respective universities, but it still doesn't make up for the fact that they are more or less presented as original reporting; without the byline, I would've taken it as a review of the study. Of course WaPo wants good sourcing, as stated in the explanatory page for the health and science section, but sourcing isn't exactly the same as taking their content.

Furthermore, the page says they're "fiercely independent from any commercial interest or advocacy group." As the KSJ article points out, that would theoretically include the universities that they're more or less doing PR for when they publish the press releases. If they're independent, they shouldn't be publishing press releases. If they are publishing press releases, they should be getting paid by the universities in question for PR.

In all honesty, this was a bit of an immature practice. I might expect this sort of thing from a less-qualified newspaper, but this is the Washington Post we're talking about, and these reporters aren't dumb or even inexperienced. As much as I don't like the idea of name-slinging just to get what you want, these reporters could easily talk to the actual researchers for original reporting. I mean, if I can get in contact with real researchers as a college student with embarrassingly little clout (and Klout…), a WaPo writer certainly could. All in all, there's no excuse.

One of the things beaten into students' heads - and I'm talking all students, not just journos - is that plagiarism in any form is bad, be it copying, lacking citations, or even just being really bad at paraphrasing. In journalism, this is especially bad because our tenets (such as those of the SPJ) include accountability and independence, both of which are undermined by using the content of others without permission.

These press releases, such as this one from the University of Zurich about attractive features and success, are labeled as being from the respective universities, but it still doesn't make up for the fact that they are more or less presented as original reporting; without the byline, I would've taken it as a review of the study. Of course WaPo wants good sourcing, as stated in the explanatory page for the health and science section, but sourcing isn't exactly the same as taking their content.

Furthermore, the page says they're "fiercely independent from any commercial interest or advocacy group." As the KSJ article points out, that would theoretically include the universities that they're more or less doing PR for when they publish the press releases. If they're independent, they shouldn't be publishing press releases. If they are publishing press releases, they should be getting paid by the universities in question for PR.

In all honesty, this was a bit of an immature practice. I might expect this sort of thing from a less-qualified newspaper, but this is the Washington Post we're talking about, and these reporters aren't dumb or even inexperienced. As much as I don't like the idea of name-slinging just to get what you want, these reporters could easily talk to the actual researchers for original reporting. I mean, if I can get in contact with real researchers as a college student with embarrassingly little clout (and Klout…), a WaPo writer certainly could. All in all, there's no excuse.

16 February 2014

Constant bio-monitoring pilot launches in Seattle in March

Bio-monitoring has been commonplace since the advent of medicine. A typical doctor's visit might include checks on pulse, blood pressure, and blood and urine proteins. Small studies based on specific conditions such as cancer use bio-monitoring to track even small changes in vitals and proteins in body fluids, and knowing what kinds of changes occur with these diseases can help doctors diagnose them earlier. One program in the UK used electronic sensors to accurately detect chemical in urine that indicate bladder cancer, a process derived from cancer-sniffing dogs and a lot less painful than the alternative of regular doctor visits to have a tube inserted in the urethra to detect tumors. Now, a study in Seattle is tracking bioindicators in healthy subjects to see if the researchers can find early indicators of illness.

This study, which starts in March, is a little out of the ordinary for a few reasons:

This study, which starts in March, is a little out of the ordinary for a few reasons:

- The healthy people are the subjects rather than the controls. Usually studies like this look at bioindicators in people who have a particular condition like bladder cancer and compare their findings to those of healthy people to see where the difference is.

- It seems to break multiple rules of standard experimentation. Not only are the healthy people not the controls, there are no controls. Everything else is blind and randomized. And participants receive feedback through the course of the study, which allows them to change how they eat, sleep, and otherwise go about their day. In a field that doesn't take well to multiple variables, this study sure has a lot of them.

- With the multiple variables comes a very thorough assessment. It'd be one thing if they just tracked changes in the blood, but that's just one facet of this study. Each of the 100 participants will have their entire genome sequenced for both genetic and epigenetic markers, physical activity tracked, sleep patterns monitored, and bodily fluids (saliva, blood, urine, and feces) examined for proteins and other chemicals.

The results from the constant bio-monitoring will be uploaded to each participant's "cloud," allowing both participant and researcher to look at the changes over the nine-month period. It may seem a bit invasive to look at so much for so long, but I see it as a way to eliminate rogue variables because it's so comprehensive. Human bodies are crazily complex, and a study like this that covers so many factors could provide some very useful information, especially if it were expanded to cover a longer time or larger population.

15 February 2014

Cambridge Science Festival makes science fun for the public

I like to think that New England is small enough to allow for big events anywhere in the six states to be common knowledge in the other five. I mean, Connecticut is two hours end to end not counting the inevitable traffic on 95 or 91, and Rhode Island is only an hour. Nevertheless, I didn't find out until a few days ago that there's a decently-sized science festival in Cambridge every spring. It's basically a big happy STEM party for an entire week in April (the 18th to the 27th this year), and it sounds amazing.

MIT, the Museum of Science, and a bunch of other institutions in Boston dedicated to science host this event, which started in 2008 and was the first event of its kind in the US at the time. Activities at the event include topics such as science in Spanish, sound science, and the science carnival and robot zoo, which are features this year. A lot of local nonprofits are involved too, such as the Boys and Girls Club, the multimedia studio NuVu, and the Women's Coding Collective, to get kids and adults alike interested in STEM. They also recruit local high schoolers to volunteer at the event, which is pretty cool.

13 February 2014

Breaking the communication barrier between scientist and civilian

As a science journalist, one of my goals is to make science more accessible to the public. There are a lot of cool things going on that people don't know about, either because they're convinced that science is scary or bad or because they think it's too hard to understand. Science can contain a lot of jargon that someone who didn't specifically take that class might not be familiar with, and even if they did take the obligatory science class, it might've been so long ago that they don't remember. There's also the issue of communication styles: journalists and such are used to the short, sweet, and to the point style of speaking, whereas scientists can tend to go into drawn-out explanations, which are inevitable given the subject matter but don't always help the audience comprehend.

I found this post today on Twitter about the tendency for researchers to explain rather than describe, and the interview that this communication consultant used illustrates the difference pretty well. It took place in January 2013 between a fiction writer and an astrophysicist, and here's what the former had to say:

I found this post today on Twitter about the tendency for researchers to explain rather than describe, and the interview that this communication consultant used illustrates the difference pretty well. It took place in January 2013 between a fiction writer and an astrophysicist, and here's what the former had to say:

"…if somebody says why does a clock tell time, you can describe the mechanism of the particular clock or you can say people arrived at a convenient definition of one day, divided it into arbitrary segments, and made a mechanism that would measure those segments because culture required timekeeping with that degree of precision. Now, that's not a complete explanation but it is explanatory whereas the other one is only descriptive."The astrophysicist responds with the idea that the "this is how it is" tendency of scientific rhetoric because their jobs are based on trying to make sense of the real world, hence the speech about how rather than the speech about why, which is what civilians generally understand better.

The issue of scientific communication and how to interact with the public is a hot topic, and while a lot of research has been done about public opinion of science (we already know that people don't trust science journalists), this weekend's American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting in Boston will have a session specifically for scientists' understanding of the public. This can then help determine the best approaches to communicating their information in an accessible way to not only inform their audience but avoid making them less liked.

12 February 2014

Tropical sea slug uses its prey against its predators

I imagine you've seen this image before; it's made its rounds of the Internet a few times, and rightfully so because this is a really cool critter.

This is the blue glaucus (Glaucus atlanticus), a member of the nudibranch clade of invertebrates. Nudibranchs are often generally characterized as sea slugs, but the ones in this clade specifically are very brightly colored, as demonstrated by this one. However, what sets the blue glaucus apart is in its behavior. The streaky blue coloration we see here is actually the underside of the animal: instead of crawling around on the ocean floor like other nudibranchs, the blue glaucus swallows air to fill its stomach, which it uses to float (admittedly upside-down) on the top of the water. The side under the water (the top) is silvery gray, so the varied coloration helps it hide from predators above and below.

If that wasn't enough, the blue glaucus and a few nudibranchs can utilize jellyfish stingers to attack their prey. This one here nibbles on the tentacles of the Portuguese man o' war, but while these jellyfish in particular are well known for their very painful sting, the blue glaucus is protected in a number of ways. Their insides are coated with a mucus that prevents the cells containing the stinger (called nematocysts) from being triggered, and cells lining their stomachs contain spindles of chitin that neutralize the stinger. The nematocysts that do survive intact are then stored and relocated to the blue glaucus' appendages for use against predators that do happen to see through the camouflage. The ability to concentrate the acquired nematocysts onto its appendages allows the blue glaucus to pack a more powerful (and potentially deadly) sting than even the Portuguese man o' war it took them from.

Accidentally threatening one of these animals would probably be like shaking hands with a friend who is wearing one of those hand shocker things from the golden days of practical jokes, except the friend is a pretty blue slug and the hand shocker could kill you.

|

| Picture from Wikimedia Commons under CC Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 |

If that wasn't enough, the blue glaucus and a few nudibranchs can utilize jellyfish stingers to attack their prey. This one here nibbles on the tentacles of the Portuguese man o' war, but while these jellyfish in particular are well known for their very painful sting, the blue glaucus is protected in a number of ways. Their insides are coated with a mucus that prevents the cells containing the stinger (called nematocysts) from being triggered, and cells lining their stomachs contain spindles of chitin that neutralize the stinger. The nematocysts that do survive intact are then stored and relocated to the blue glaucus' appendages for use against predators that do happen to see through the camouflage. The ability to concentrate the acquired nematocysts onto its appendages allows the blue glaucus to pack a more powerful (and potentially deadly) sting than even the Portuguese man o' war it took them from.

Accidentally threatening one of these animals would probably be like shaking hands with a friend who is wearing one of those hand shocker things from the golden days of practical jokes, except the friend is a pretty blue slug and the hand shocker could kill you.

11 February 2014

Around the world study provides evidence of more fish than predicted

While I haven't always appreciated the nudges toward vegetarianism/veganism that come naturally with living in Ithaca, especially when they've come from some of the biology department professors, it is helpful to know about and understand the human culinary impact on the biosphere. In my oceanic islands class in the fall, we watched a documentary about how our appetites via overfishing and unsustainable fish farming are decimating the wild populations, and while it didn't prevent me from stocking up on seafood when I went back home, it was certainly something to think about. Without watching how and what we catch, we could be in big trouble.

Or are we? Some studies show a massive decline in stocks of certain species and locations, such as those featured in End of the Line, but a newly published study in Nature Communication suggests that those numbers are underestimating the number of mesopelagic fish. These fish, which include the highly prolific lantern fishes, live between 200m and 1000m below the surface of the water. Current estimates predict that fish in this zone make up about 1 billion tons of biomass - lanternfish alone account for more than 600 million tons of that

Keep in mind that lanternfish like the one above range from 3 to 35cm, so even if we're talking 600 million tons of lanternfish biomass alone, that would mean at the very least 1.2 trillion fish, assuming that they're each a pound, and I highly doubt the 3cm ones are that heavy. Data from the Malaspinas Expedition (heads up: site is in Spanish) that tracked the biodiversity of the open and deep ocean in 2010-2011 is suggesting that estimate is only a tenth of what's actually out there. I know these fish aren't huge, but 12 trillion fish is a lot for one type of fish.

Or are we? Some studies show a massive decline in stocks of certain species and locations, such as those featured in End of the Line, but a newly published study in Nature Communication suggests that those numbers are underestimating the number of mesopelagic fish. These fish, which include the highly prolific lantern fishes, live between 200m and 1000m below the surface of the water. Current estimates predict that fish in this zone make up about 1 billion tons of biomass - lanternfish alone account for more than 600 million tons of that

|

| Picture from Emma Kissling on Wikimedia Commons via public domain. |

Moral of the story: start eating lanternfish fillets? Start catching; you're going to need a lot.

10 February 2014

Citizen science emerges through gaming

I think it's fair to say that gaming has become a significant part of the human experience, from athletic events and board games to RPGs and video games. Anyone needing recent proof can look at the examples of Candy Crush Saga addiction and the uproar that ensued when the creator of Flappy Bird decided a few days back to remove the game from the market due to the pressures associated with running such a viral enterprise. At the same time, games aren't just the subjects of obsession but a way to socialize with friends (and make new ones), spark imaginations, and even cure cancer.

Alright, so the last one was a bit of a stretch, but Cancer Research UK teamed up with developers from Facebook, Amazon, and Google to create "Play to Cure: Genes in Space," which could lead to a cure later on. The free game, which is available on Apple and Android products, is based on mapping routes through space to gather the valuable Element Alpha. While players fly through space, shoot down dangerous asteroids, and upgrade their ships, they're actually analyzing genetic data that can be later used for developing cancer treatments. The game itself was developed at a game jam last year, just like the one a few weekends ago but specific to the goal of creating a data-analyzing game for cancer research.

The professor I talked to for my Global Game Jam article is currently working on something similar that uses an adventure-style game to perform taxonomic classification. The line that stuck for me from him was that the goal is to create games that allow people to do something while they play, even scientific work, without realizing it.

Without throwing everyone under the proverbial bus, I think the reason why more citizen science hasn't come to the forefront is because of a lack of interest in putting forth actual work; I have SETI running on my computer as a screensaver, so I'm contributing to their database, but I wouldn't get all hyped up about number-crunching that data myself. However, if the scientific aspect is hidden in a fun format like Play to Cure and the taxonomic one, there could be a lot of potential.

Alright, so the last one was a bit of a stretch, but Cancer Research UK teamed up with developers from Facebook, Amazon, and Google to create "Play to Cure: Genes in Space," which could lead to a cure later on. The free game, which is available on Apple and Android products, is based on mapping routes through space to gather the valuable Element Alpha. While players fly through space, shoot down dangerous asteroids, and upgrade their ships, they're actually analyzing genetic data that can be later used for developing cancer treatments. The game itself was developed at a game jam last year, just like the one a few weekends ago but specific to the goal of creating a data-analyzing game for cancer research.

The professor I talked to for my Global Game Jam article is currently working on something similar that uses an adventure-style game to perform taxonomic classification. The line that stuck for me from him was that the goal is to create games that allow people to do something while they play, even scientific work, without realizing it.

Without throwing everyone under the proverbial bus, I think the reason why more citizen science hasn't come to the forefront is because of a lack of interest in putting forth actual work; I have SETI running on my computer as a screensaver, so I'm contributing to their database, but I wouldn't get all hyped up about number-crunching that data myself. However, if the scientific aspect is hidden in a fun format like Play to Cure and the taxonomic one, there could be a lot of potential.

08 February 2014

Scientists still speculating what makes ice slippery

This one accidentally relates to the Olympics too, but only because there is a lot of ice involved with some of the events. Science Friday did a segment this week about what makes ice slick, but what I found interesting is that scientists still aren't entirely sure what allows us to skate, ski, or throw a big rock across it. The general consensus is that there's a very thin layer of water on top of the ice that reduces friction, but how that layer forms is contested.

The segment's guest, who is a mechanical engineering professor, explained that the reasoning in most physics books is actually wrong: they claim that the water is produced by the pressure created by the weight of the person (or curling stone) because liquid water is more dense than frozen water. In reality, it would take a lot more weight than the average skater to create the pressure required. Currently, there are two other possible explanations for the water:

The segment's guest, who is a mechanical engineering professor, explained that the reasoning in most physics books is actually wrong: they claim that the water is produced by the pressure created by the weight of the person (or curling stone) because liquid water is more dense than frozen water. In reality, it would take a lot more weight than the average skater to create the pressure required. Currently, there are two other possible explanations for the water:

- Ice just naturally has a nanoscale layer of water on its surface (we're talking a thousandth of the width of a hair) that provides the slipperiness, or

- The friction generated from the initial movement generates enough energy to melt the surrounding ice.

The former may seem a bit farfetched, but it's been shown to exist even tens of degrees below freezing, so it helps to explain why we can slip on ice not only when it's super cold but even if we're not moving, which the latter wouldn't be able to account for.

Of course, in Sochi, the problem isn't making the ice warm enough to produce that layer (because it's already there…) but rather keeping the venues cold enough, between the subtropical location and the not-so-finished states of the facilities...

A quick PSA regarding photos

Regular posting will resume tonight, but I wanted to make a quick announcement. If anyone has archive-binged recently, you may notice that some of the pictures have changed or been deleted. I did this yesterday to correspond to an article I received regarding photo use and copyright. As a more or less broke college student, I don't exactly have the funds to go against a copyright lawsuit, and even though I doubt anyone would go through my stuff specifically to throw me under the bus, it could very well happen. As such, pictures, graphics, and so on on here from now on are either mine, belonging to someone I know, public domain, or via Creative Commons. I have also applied a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license to mine (though I could've sworn I did that earlier, but it appears I didn't).

Thanks for hanging in there. I'll have a full post tonight.

Thanks for hanging in there. I'll have a full post tonight.

07 February 2014

Kicking off the Olympics with science

What else would I do, aside from make corny jokes about how my female axolotl and the host city in Russia are pronounced the same and differ only in one letter?

The CBC has a whole playlist of Olympic-themed science videos, including stats on your chances of making it to the Games and what factors impact performance. They make a good point that I've observed watching sports in general. Football players look like they could crush me by sitting on me, baseball players look like they could throw me, and gymnasts/figure skaters look like I could throw them. There's also the question of age: I understand the body works at an optimal level for only so long and therefore prevents older people from competing in certain sports, but it's getting to the point where you'll have middle schoolers competing in the Olympics and retired before they go to college. At least they'll be able to pay for school, I guess.

Popular Science also has a good amount of Sochi coverage from the cover story of their February issue, "Engineering the Ideal Olympian." It includes segments about wind tunnels used for training ski jumpers (which was of significance for this year because this is the first time women are allowed to compete in the ski jumping event), using race car design knowledge to create a faster bobsled (if only it were for the Jamaican team), and a good chart detailing the common injuries that occur in the Winter Olympics.

With the opening ceremony today, I felt it was necessary to have a themed post, and when I found this video about how Olympian body types have changed over the years, I thought that would be a good place to start:

The CBC has a whole playlist of Olympic-themed science videos, including stats on your chances of making it to the Games and what factors impact performance. They make a good point that I've observed watching sports in general. Football players look like they could crush me by sitting on me, baseball players look like they could throw me, and gymnasts/figure skaters look like I could throw them. There's also the question of age: I understand the body works at an optimal level for only so long and therefore prevents older people from competing in certain sports, but it's getting to the point where you'll have middle schoolers competing in the Olympics and retired before they go to college. At least they'll be able to pay for school, I guess.

Popular Science also has a good amount of Sochi coverage from the cover story of their February issue, "Engineering the Ideal Olympian." It includes segments about wind tunnels used for training ski jumpers (which was of significance for this year because this is the first time women are allowed to compete in the ski jumping event), using race car design knowledge to create a faster bobsled (if only it were for the Jamaican team), and a good chart detailing the common injuries that occur in the Winter Olympics.

06 February 2014

Plagues helped shape human genomes

Genetics has always been my favorite part of biology. I enjoy Punnett squares more than I really should (as I explain in this post about my first batch of axolotl eggs), I got to compare my mitochondrial DNA to an international database that included Neanderthal DNA in my genetics class last spring, and overall I find inheritance and genes to be really interesting. As such, this post from IFLS about how the Black Death tweaked European and Rroma genomes was something I wanted to look into.

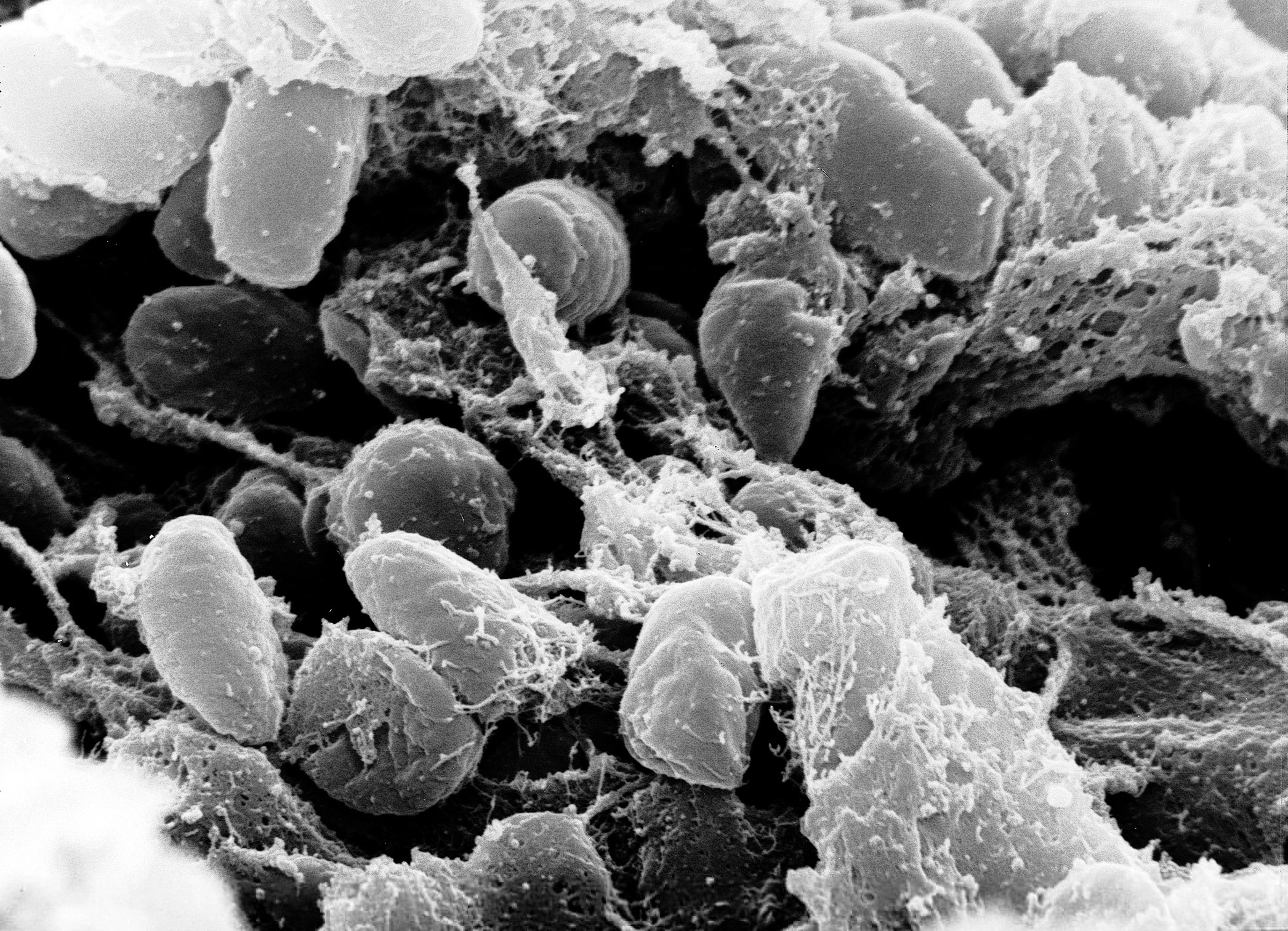

What these researchers found was that the presence of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for killing off more than 20 percent of the world's population at the time, selected for genes involved in the immune response, specifically a Toll-like receptor that helps in the pathway to tell the cell that it is under attack. As one might guess, people in the 1300s who didn't have these genes were killed by the plague, while those who did survived and passed on these genes to their children. It's natural selection for humans.

The cool part? This selection happened in two genetically distinct populations. While Europeans and Rroma both lived in Europe, the Rroma were originally from the northwest corner of India, so their initial geographic isolation from the native European group provided for a greater genetic diversity between the two groups. However, because they occupied the same space during the wrath of the Black Death, both were subject to the natural selection process above, thus picking out the immune people from both populations. Because these genes came about separately (geographic isolation and all), this shows convergent evolution; another example of this process would be how birds, bats, and bugs all have wings, but they all developed them separately rather than inheriting them from a common flying ancestor.

What these researchers found was that the presence of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for killing off more than 20 percent of the world's population at the time, selected for genes involved in the immune response, specifically a Toll-like receptor that helps in the pathway to tell the cell that it is under attack. As one might guess, people in the 1300s who didn't have these genes were killed by the plague, while those who did survived and passed on these genes to their children. It's natural selection for humans.

|

| The nasty little bacterium responsible for decimating Europe. Public domain photo from the NIH |

So no, we don't have bacterial DNA in our genome (… alright, technically we do because some of the genes are the same for all organisms, but you get my drift), but this goes to show that even a small organism like this can bring about large changes in human genetic history.

05 February 2014

Science and religion go head to head in creation debate

I had all intentions of watching the creation debate between Bill Nye and Ken Ham yesterday, but the combination of a Spanish paper and the YouTube page crashing my computer prevented me from watching it and thus covering it until now. I've since caught bits and pieces, and in addition to seeing other commentaries on it, I'd like to address a few things that I feel make this discussion worth having.

Regarding bias, I feel it's pretty obvious where I stand in this debate, between my explicit interest in science and my "not so explicit but potentially assumed" status as an atheist, but I will do my best to keep this as civil as possible because nothing can get done otherwise. Also, for simplicity's sake, I'll refer to the people on Nye's side as "evolutionists" and Ham's side as "creationists" because while Nye is a scientist, there are scientists who may not believe in evolution (which, admittedly, is a stretch, but for the sake of the argument).

Regarding bias, I feel it's pretty obvious where I stand in this debate, between my explicit interest in science and my "not so explicit but potentially assumed" status as an atheist, but I will do my best to keep this as civil as possible because nothing can get done otherwise. Also, for simplicity's sake, I'll refer to the people on Nye's side as "evolutionists" and Ham's side as "creationists" because while Nye is a scientist, there are scientists who may not believe in evolution (which, admittedly, is a stretch, but for the sake of the argument).

- Evolutionists are more willing to say "I don't know," and creationists need an explanation for everything. This was made apparent in this Buzzfeed article that was in my news feed, in which the author asked creationists at the debate to pose questions to the evolutionists. The lady in photo number 9 illustrates this point very well in her question, "If God did not create everything, then how did the first single-celled organism originate? By chance?" Evolutionists would say yes, and creationists would say that such an instance couldn't possibly happen, hence the position of God as creator of these organisms.

- Evolutionists are more open to changing their outlook, and creationists are solid in their beliefs. Part of the scientific process is revisiting old hypotheses and changing them if outcomes or observations refute them; as such, scientists would be willing to accept another hypothesis were evidence to arise that disproved evolution, whereas no amount of evidence supporting evolution will change a creationist.

- Only a minor thing, but the creationist side can't really claim persecution in education when the educational systems that teach creationism only look at the Christian story. Other beliefs are snubbed, as demonstrated by a quick Google search of "creation story."

This seems to fit in with the bit of not changing what they think when other options are provided.

- This is probably the most important, but science and religion aren't completely separate. I know people who are comfortable in their faith and still accept evolution as more or less fact, and even though the church system seems to be anti-science in some respect throughout the ages, some of the best science has come out of it. Take Mendelian genetics for example: without it, we wouldn't know how inheritance works, yet Gregor Mendel was a monk.

As always, I'm open for discussion. What are your thoughts on the debate, evolution, or creationism?

03 February 2014

Japanese researchers develop new way of creating stem cells

This is pretty monumental, and I'm kicking myself for not getting to it sooner. Stem cells, specifically pluripotent stem cells, are a current scientific target because they have the proverbial "blank slate:" like a theoretical infant that can become a doctor, firefighter, or animal trainer, these cells can differentiate into anything in the future, be they stomach cells, brain cells, or blood cells. As such, they are extremely useful, such as in organ regeneration and transplants (another issue close to home, plus they covered it tonight on the Science Channel), but at the same time, they are surrounded by controversy because for the longest time, the only source was embryonic tissue.

As published last week in Nature, a team of scientists in Japan have found a way to reprogram body cells into pluripotent stem cells. They determined that exposing mammalian somatic cells to a strong external stimulus, like acid, reprogrammed these cells without the introduction of a new nucleus or different molecules to transcribe the DNA into RNA. This was a previously unknown mechanism, but further studies showed that these reprogrammed cells, called STAP cells (STAP standing for stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency), have a lot less DNA methylation. While somatic cells would normally have genes not applicable to their function turned off (i.e. a nerve cell turning off eye-related genes), STAP cells don't have as many genes turned off and can therefore fill different functions.

Admittedly, I'm most excited about the use of this for organ regeneration because this would reduce a lot of transplant-related problems. For example, it can allow doctors to take a donor's heart, take out all of the muscle cells it so only the connective tissue is left, and fill in the heart with the patient's own muscle cells (here derived from somatic cells that were converted into STAPs and induced into being muscle cells). This would prevent any chance of rejection because it's the patient's own cells and thus allow the patient to carry on without having to take anti rejection meds and then be restricted as to what they can do.

As published last week in Nature, a team of scientists in Japan have found a way to reprogram body cells into pluripotent stem cells. They determined that exposing mammalian somatic cells to a strong external stimulus, like acid, reprogrammed these cells without the introduction of a new nucleus or different molecules to transcribe the DNA into RNA. This was a previously unknown mechanism, but further studies showed that these reprogrammed cells, called STAP cells (STAP standing for stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency), have a lot less DNA methylation. While somatic cells would normally have genes not applicable to their function turned off (i.e. a nerve cell turning off eye-related genes), STAP cells don't have as many genes turned off and can therefore fill different functions.

Admittedly, I'm most excited about the use of this for organ regeneration because this would reduce a lot of transplant-related problems. For example, it can allow doctors to take a donor's heart, take out all of the muscle cells it so only the connective tissue is left, and fill in the heart with the patient's own muscle cells (here derived from somatic cells that were converted into STAPs and induced into being muscle cells). This would prevent any chance of rejection because it's the patient's own cells and thus allow the patient to carry on without having to take anti rejection meds and then be restricted as to what they can do.

02 February 2014

NFL experts (finally) recognize the dangers of concussions

Super Bowl football Broncos Seahawks yay rah rah. I spent the game at rehearsal and playing the online version of Cards Against Humanity. I've never been a huge fan of football in general; I only know as much as I do from four years of high school marching band and a gym teacher who was more forgiving to the less athletic among us and gave us comprehension quizzes rather than grading by ability. What I do know is that people care way too much about it (i.e. our HS football team got new jerseys every year while the softball team had to buy their own med kits for crying out loud), and that it is a lot more dangerous than people like to think.

I think it's a false sense of security. Before you even leave the locker room, you drown yourself in "protective" padding, and then you put a big bowl around your head with only enough holes to see through and barely hear through. Because of these extra layers, players think they can ram into each other like bumper cars because they're "protected," yet we're seeing more injuries and deaths related to neurological trauma. Sure, going full-force into another person without the gear would do a lot more damage, but it's not going to protect you from everything.

Finally, the NFL is starting to recognize that hey, concussions and traumatic brain injuries are a real problem. The NFL Head, Neck, and Spine Committee have been working not only to make the game safer but also to spread awareness of the dangers of these injuries. These have included informational posters in middle- and high schools, sideline neurologists, and advocating for a "when in doubt, sit them out"-type law in youth football that has passed in every state but Mississippi. The committee is also working to raise awareness for concussions in all activities using football as a role model of sorts.

Unfortunately, it has taken a multimillion-dollar lawsuit from former players and the deaths of others to bring this to the limelight, but the sooner they deal with this, the better.

I think it's a false sense of security. Before you even leave the locker room, you drown yourself in "protective" padding, and then you put a big bowl around your head with only enough holes to see through and barely hear through. Because of these extra layers, players think they can ram into each other like bumper cars because they're "protected," yet we're seeing more injuries and deaths related to neurological trauma. Sure, going full-force into another person without the gear would do a lot more damage, but it's not going to protect you from everything.

Finally, the NFL is starting to recognize that hey, concussions and traumatic brain injuries are a real problem. The NFL Head, Neck, and Spine Committee have been working not only to make the game safer but also to spread awareness of the dangers of these injuries. These have included informational posters in middle- and high schools, sideline neurologists, and advocating for a "when in doubt, sit them out"-type law in youth football that has passed in every state but Mississippi. The committee is also working to raise awareness for concussions in all activities using football as a role model of sorts.

Unfortunately, it has taken a multimillion-dollar lawsuit from former players and the deaths of others to bring this to the limelight, but the sooner they deal with this, the better.

01 February 2014

FAA approves astronaut training program

I'm still mesmerized by the programming that NASA, ESA, and other space-based research has put out. I mean, we've put people on the moon, rovers on other planets, and probes beyond the reaches of our solar system. We have telescopes that can see billions of light years away in wavelengths beyond human perception. And now we have astronaut training for the general public.

Waypoint 2 Space, which is based at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, just got FAA approval for multiple space training programs. These are broken into 3 parts:

Waypoint 2 Space, which is based at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, just got FAA approval for multiple space training programs. These are broken into 3 parts:

- Level 1: Spaceflight Fundamentals. It's a one-week intro course in astronaut things like suit fittings, G-force and microgravity activity, terrain navigation with rovers, and physiological effects of being in space.

- Level 2: Sub-Orbital Training. This one is three days and covers how to deal with the effects of rocket-powered flight, like G-forces and weightlessness, as well as how to handle any emergency situations like hypoxia or smoke.

- Level 3: Orbital Training. The most intensive part of their offerings, this lasts eight weeks or twelve weeks with training outside the orbiter. It prepares trainees for life in space with an emphasis on test scenarios for situational awareness, like if they were to become disoriented depressurized.

These trips aren't cheap; Level 1 training runs around $45,000, and the other two aren't available to the public just yet. However, I think it's a great opportunity for people to give space training a go, and it's a lot cheaper than the Virgin Galactic trip (though admittedly that would be really cool too).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)